In our article of 20th May we commented about how the UK government had sold a bond (government debt) with a negative yield. We went on to explain that in practise, this means that the government is being paid to look after investors money, rather than having to pay to investors for the benefit of borrowing their money.

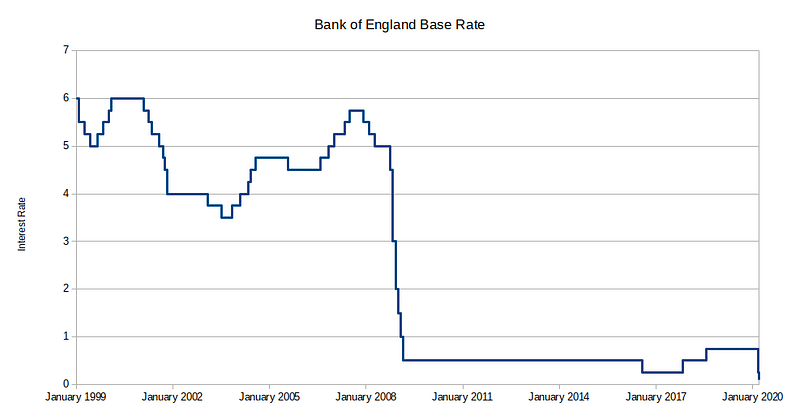

During the ongoing coronavirus disruption we’ve seen the Bank of England reduce the interbank overnight borrowing rate (Bank of England Base Rate) to a new record low, but is it at the bottom?

The graph above shows the dramatic and sustained fall in Bank of England Base Rate from the time of the global credit crunch and resultant financial crises, however the trend of falling base rate is long established, as can be seen by the chart below which plots base rate from 1979 to 2010:

What does this tell us? It tells us that the overall 40 year trend is for falling interest rates.

Over recent months there has been much speculation about the likelihood of the Bank of England reducing interest rates from the current historic low of 0.10% to zero, or a minus rate and the risk of us, regular folk, having to pay fees for the privilege of letting banks look after our money.

In this guest article, Professor Panicos Demetriades, Professor of Financial Economics at the University of Leicester explains why he thinks the Bank of England doesn’t need to worry about negative interest rates……yet:

Bank of England is considering negative interest rates

– it doesn’t need to yet

Central banks are stretched to the limit, trying to support the economy during the unprecedented COVID-10 recession. The Bank of England is now considering cutting its base rate to below zero. The bank has so far shied away from negative rates, not least because they are much harder to explain to the public and the banks, whose technology systems may not even be able to handle this change.

At 0.1%, the current base rate is already lower than it has ever been. The decision was made in March 2020 when the bank acted aggressively to ease the pain inflicted on the economy by the coronavirus pandemic.

Besides cutting rates to unprecedented levels, the bank also expanded its bond purchase programme, known as quantitative easing or QE. QE has been used by all major central banks as an alternative to cutting rates below zero. It involves largescale purchases of financial assets, which raises their price and reduces yields.

Major central banks around the world have used QE, including the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, as an effective way to boost liquidity and confidence in markets, while allowing financial institutions to rebalance their portfolios. It has helped central banks to prevent deflation – a negative spiral of falling prices, increasing debt burdens and insolvencies.

But even QE has its limits. There are only so many financial assets that a central bank can buy without putting taxpayer money at risk. QE expands central bank balance sheets, which ultimately means bigger risks for taxpayers and higher asset prices – making monetary policy more political than is normally the case, by making asset holders wealthier.

Running out of fire power

There’s a risk that negative interest rates will hurt bank lending and financial stability. Hence, central banks normally avoid this territory – unless they are running out of firepower.

Negative rates can result in savers and investors hoarding cash. After all why would anyone put their savings in a bank if it means that it loses value compared to cash? If people hoard cash, banks will have less money to lend to firms and households. This cannot be a good thing for the economy.

Bank profits will inevitably be affected – and that may make the financial system more fragile and prone to crises. Cutting into bank profits may sound good but the reality is that weaker banks are a headache for policymakers and a big risk for taxpayers, as big banks are often bailed out with taxpayers’ money to prevent financial meltdown.

So why is the Bank of England considering using negative rates now? Well, one obvious reason is that QE has reached its limits and the economy remains in deep recession. Another reason is that other central banks have used it with some success.

For example, the European Central Bank’s deposit facility inflicts a penalty of 0.5% per annum for banks using it. This discourages banks from parking their excess reserves with the central bank and instead encourages them to lend at positive but low rates. Meanwhile, the ECB’s main refinancing rate – what banks pay to borrow from the ECB – has been 0% since 2016, so banks themselves do not pay a negative rate to borrow from the ECB.

This model offers a possible blueprint for the Bank of England. It could reduce the base rate to 0% and charge banks when they choose to keep their reserves at the Bank.

Read more: Lessons from the 2008 financial crisis for our coronavirus recovery today – Recovery podcast series part six

Alternative to negative rates

But in my view there is an alternative involving a more aggressive use of forward guidance. Forward guidance is when a central bank is more active in explaining the likely future course of its rate policy decision-making. It can make a big difference when it comes to investment decisions, which depend not only on current rates but also on their future levels.

For example, if businesses and households know that rates will remain at the current low levels for the next two to three years, they will be more likely to borrow and spend more. This is because they will be certain that borrowing costs will remain low into the foreseeable future – exactly what is needed to stimulate the economy in a deep recession.

In fact the ECB started using forward guidance in 2013 – well before it launched its asset purchase programme – and continues to do so today. Its forward guidance has been effective in lowering long-term rates and has helped to anchor expectations on the future path of interest rates.

In contrast to the ECB, the Bank of England has not used forward guidance on rates very much. Perhaps the change of governor in March 2020 made it reluctant to make any big commitments. But now, with Andrew Bailey in post and nearly eight years of his term ahead of him, a commitment to low rates for an extended period makes a lot of sense. And it would help the bank to avoid entering controversial negative interest rate territory.

This guest blog is republished under a Creative Commons license with grateful thanks